- Home

- Rick Riordan

The Last King of Texas - Rick Riordan Page 13

The Last King of Texas - Rick Riordan Read online

Page 13

DeLeon yanked the Polaroid off the computer screen. "Bastards."

"Locker-room humor."

"Oh, yeah. Me and the boys — we're tight. We snap each other's butts with towels all the time."

I tried not to picture that. "Be a lot worse if they just ignored you."

"You're just the expert on everything, aren't you, Navarre? You and your friend Mr. Air-Force-Special-Police."

"About last night—"

"Save it."

She began shuffling papers with a vengeance, clearing her in box, taking down little stickie notes and division memos that adorned the fabric walls. As the first layer of paper came down, personal stuff was unearthed — a photo of DeLeon getting awarded her detective's shield, a framed B.S. in criminal justice from UT, a picture of her as an air force cadet.

Two things surprised me. One was a photocopy of a Pablo Neruda love poem, "Te Recuerdo Como Eras." The other was a tiny framed picture of a female police officer who looked like a heavier, lighter-skinned version of Ana DeLeon. By the color of the photo and the style of the woman's hair and uniform, I placed the photo circa 1975.

"Your mom?"

DeLeon glanced at it, then shoved another folder across her desk. "Yes."

She kept sorting papers, her eyes glassy.

"You okay?"

She glared at me, then pulled a color photo out of a case file and flicked it up at me with two fingers. "This is how okay I am."

All I saw in the photograph at first were glaring browns and reds. Then my mind made sense of the shapes and I pulled back, repulsed. It was a young child, African American, murdered and displayed in a way my mind comprehended but refused to process into complete thoughts.

"Jesus."

She slid the picture back into the file. "Good thing I was called away from our wonderful evening. Between the Brandon case and a couple of other things the Night CID couldn't handle I got that lovely call. Girl was three."

I swallowed, closed my eyes. The image wouldn't go away.

"No mystery," DeLeon said. "What was it the lieutenant said, a two plus two? Stepdad was a crack addict. Started yelling at the mom because she was stealing his money. It went downhill from there. Young victims. That's why I got out of sex crimes. Now here I am again — otra vez."

DeLeon focused on her blank computer screen. "So what am I supposed to do? I'm supposed to get things in order and take a couple of days off. Simple."

"Hernandez is in a tough spot. Sure you don't want to catch some dinner?"

"Hernandez does what he can. And yes, I'm sure."

"If you needed a little help on the Sanchez follow-up—"

"I'd what? Share information with you? And every damn private investigator in town would be knocking on my door anytime he needed help. The newspapers would be screaming about how we couldn't handle our own cases. No thanks."

"We want the same answers."

"Great. You find out something on your own, come in and make another statement. That's all you are, Navarre: another witness with a statement."

"That why you brought me into the interrogation room?"

She paused. "It was a gamble."

"Gamble again. I have a friend who might help. People don't like talking to cops, they might talk to my friend."

"I don't like your friend."

"I don't mean George Berton."

"Neither do I. I know about Ralph Arguello."

I'd heard police officers speak Ralph's name many times, never lovingly, but DeLeon's tone held a lot more poison than I would've expected.

"You've had the pleasure of Ralph's acquaintance?"

She shot me another cold look, but underneath something was crumbling, eroding. "Will you get out of here, please?"

"Here's an idea. I'll ask if you're giving me a firm 'no' on poking around about the Brandon murder. You don't respond. I'll take that as a silent, completely off-the-record consent and we'll go from there. I'll keep you posted. So how about it — can I look around on the Brandon murder?"

"No."

"You're not getting the subtle innuendo routine, here."

She raised her voice a half octave. "Just go."

"Get some sleep one of these days, okay?"

"Leave."

I left her at her desk, shuffling through files and photos with what looked like aimlessness. A shudder went through my nervous system, the aftershock from the photo of the murdered child. I found myself reviewing lines from the Neruda love poem on DeLeon's cubicle wall, wondering how it had made its way there amid the paperwork of violence — "I Remember You As You Were."

I made a beeline out of the neutral gray and the fluorescents of SAPD homicide, heading toward the outside — toward smells and color and moving time. I wanted to see if it was nighttime yet. I had a feeling it might be.

TWENTY

Drifting along the sidewalk in front of police headquarters was the usual parade of undesirables — cons, thugs, derelicts, undercovers pretending to be derelicts, derelicts pretending to be undercovers pretending to be derelicts.

They collected here each evening for many reasons but hung around for only one. They knew as surely as those little white birds hopping around on the crocodile's back that their very proximity to the mouth of the beast made them safe.

Patrol cars were parked along West Nueva. Inside the barbed wire of the parking lot, in a circle of floodlight, five detectives in crisp white shirts and ties and side arms were having a smoke. Outside the fence a couple of cut-loose dealers were trading plea-bargain stories.

I walked across Nueva to the Dolorosa parking lot, got in the VW, and pulled onto Santa Rosa, heading north. I made the turn onto Commerce by El Mercado, then passed underneath I-10 — over the Commerce Street Bridge, into the gloomy asphalt and stucco and railroad track wasteland of the West Side. Ahead of me, the sunset faded to an afterglow behind palm trees and Spanish billboards. Turquoise and pink walls of icehouses and bail bond offices lost their color. On the broken sidewalks, men in tattered jeans and checkered shirts milled around, their faces drawn from an unsuccessful day of waiting, their eyes examining each car in the fading hope that someone might slow down and offer them work.

I turned north on Zarzamora and found the place where Jeremiah Brandon had died a mile and a half up, squatting between two muddy vacant lots just past Waverly. Patches of blue stucco had flaked off its walls, but the name was still visible in a single red floodlight — POCO MAS — stenciled between two air-conditioner units that hung precariously from the front windows.

The building was tall in front, short in back, with side walls that dropped in sections like a ziggurat. Tejano music seeped through the hammered tin doorway.

Two pickup trucks, a white Chevy van, and an old Ford Galaxie were parked in the gravel front lot. I pulled the VW around the side, into the mud between a Camry with flat tires and a LeBaron with a busted windshield, and hoped I hadn't just discovered the La Brea tar pit of automobiles.

The rest of the block was lined with closed tiendas and burglar-barred homes. Crisscrossed telephone lines and pecan tree branches sliced up the sky. The only real light came from the end of the block across the street — the Church of Our Lady of the Mount. Its Moorish, yellow-capped spires were brutally lit, a dark bronze Jesus glaring down from on high at the Poco Mas. Jesus was holding aloft a circle of metal that looked suspiciously like a master's whip. Or perhaps a hubcap rim.

At the entrance to the cantina, I was greeted by a warm blast of air that smelled like an old man's closet — leather and mothballs, stale cologne, dried sweat and liquor. Inside, the rafters glinted with Christmas ornaments. Staple-gunned along the walls were decades of calendars showing off Corvettes with bras and women without. The jukebox cranked out Selena's "Quiero" just loud enough to drown casual conversation and the creaking my boots must've made on the warped floor planks.

I got a momentary, disapproving once-over from the patrons at the three center tables. The men were hard-faced Latinos

, most in their forties, with black cowboy hats and steel-toed boots. The few women were overweight and trying hard to pretend otherwise — tight red dresses and red hose, peroxide hair, large bosoms, and chunky faces heavily caked with foundation and rouge designed for Anglo complexions. Long neck beer bottles and scraps of bookie numbers littered the pink and white Formica.

On a raised platform in back were two booths, one empty, one occupied by a cluster of young locos — bandannas claiming their gang colors, white tank tops, baggy jeans laced with chains, scruffy day beards. One had a Raiders jacket. Another had a porkpie hat and a pretty young Latina on his lap. The girl and I locked eyes long enough for Porkpie to notice and scowl.

Then I recognized someone else.

Hector Mara, Zeta Sanchez's ex-brother-in-law, was talking to another man at the bar.

Mara wore white shorts and Nikes and a black Spurs tunic that said ROBINSON. His egg-brown scalp reflected the beer lights.

Mara's friend was thinner, taller, maybe thirty years old, with a wiry build and a high hairline that made his thin face into a valentine. He had a silver cross earring and black-painted fingernails, a black trench coat and leather boots laced halfway up his calves. He'd either been reading too much Anne Rice or was on his way to a bandido Renaissance festival.

A line of empty beer bottles stood in front of the two men. Mara's face was illuminated by the little glowing screen of a palm-held computer, which he kept referring to as he spoke to the vampire, like they were going over numbers. I climbed onto the third bar stool next to Mara, and spoke to the bartender loud enough to be heard over Selena. "Cerveza, por favor."

Mara and the vampire stopped talking.

The bartender scowled at me. His face was puffy with age, his hair reduced to silver grease marks over his ears. "Eh?"

"Beer."

He squinted past me suspiciously, as if checking for my reinforcements. Hector Mara just stared at me. Huge loops of armhole showed off his well-muscled shoulders, swirls of tattoos on his upper arms, thick tufts of underarm hair. He had an old gunshot scar like a starburst just above his left knee. The vampire stared at me, too. He clicked his black fingernails against the bar. Friendly crowd.

"Unless you've got a special tonight," I told the bartender. "Manhattan, maybe?"

The bartender reached into his cooler, opened a bottle, then plunked a Budweiser in front of me.

"Or beer is fine," I said.

"Eh?"

I made the "okay" sign, dropped two dollars on the counter. Without hesitating, the old man got out a second beer and plunked it next to the first. I was tempted to put down a twenty and see what he'd do. Instead I slid one of the Buds toward Hector Mara.

"Maybe your friend could go commune with the night for a few minutes?" I suggested.

Mara's face was designed for perpetual anger — eyes pinched, nose flared, mouth clamped into a scowl. "I know you?"

"I saw Zeta today."

Mara and the vampire exchanged looks. The vampire studied my face one more time, memorizing it, then detached himself from the bar. He flicked his fingers toward the cholos in the back booth and they all lifted their chins. The vampire walked out.

I watched him get into the white Chevy van and drive away.

"Yo, gringo," Hector Mara said, "You got any idea who you just offended?"

"None. Much more fun that way. Although if I was guessing, I'd say it was Chich Gutierrez, your business partner."

Mara's eye twitched. "Who the fuck are you?"

"I was at that party you threw yesterday out on Green Road. The one where Zeta blew a hole in the deputy."

Mara's eyes drifted down to my boots, then made their way back up my rumpled dress clothes, my face, my uncombed hair.

"You ain't a cop," he decided.

"No."

"Then fuck off."

He pushed the beer back toward me and returned to his PalmPilot, started tapping on the screen with a little black stylus. On the jukebox, Selena segued into Shelly Lares.

I looked at the bartender. "Donde esta the famous spot?"

"Eh?"

"The place where Zeta Sanchez killed Jeremiah Brandon."

The bartender waved his hands adamantly. "No, no. New management."

He said it like a foreign phrase he'd been trained to speak in an emergency. Mara pointed over his shoulder with the stylus. "Second booth, gringo. The one that's always empty."

The bartender mumbled halfheartedly about the change of management, then retreated to his liquor display and began turning the bottles label-out.

"The D.A.'s going to prosecute," I told Mara.

"Big surprise."

"They figure ten to ninety-nine for shooting the deputy, life for Aaron Brandon's murder, maybe federal charges for the bomb blast. Quick and easy. That's before they even consider the Old Man's murder case from '93."

"Hijo de puta like you gonna love that."

"And who am I?"

A stripe of green neon drifted across Mara's forehead as he turned toward me. His eyes burned with loathing. "Reporter. Got to let those nervous gringos see the right headline, huh? Mexican Convicted for Alamo Heights Murder."

I pulled out one of my Erainya Manos Agency cards, slid it across the counter.

"What if I thought Sanchez was framed?"

Mara's bad-ass expression melted as soon as he saw the card. He looked from it to me. "The guy in the Panama hat."

"George Berton."

Mara pushed the card away, then leaned far enough toward me so I could smell the beer on his breath.

"I told your friend," he hissed. "I said I'd think about it. All right? Don't push me."

I tried to stay poker-faced. It wasn't easy.

"Sure," I said. "I was just in the neighborhood. Thought I'd check back."

Mara sniffed disdainfully. He gestured toward the back of the room and the screen of his PalmPilot flashed like mercury. "You see the locos in the corner? No, man, I don't mean look at them. They'll think you want trouble. Those are Chich's boys. His younger set. You think I'm going to sit here and talk friendly with them watching us, you're crazy."

"Make small talk. Were you in this place the night Jeremiah Brandon got shot?"

"I—" Hector looked down at the bar. "No. I missed it. Most righteous thing that ever happened in this place."

"I can understand why you'd think that."

"Oh, you can."

"The old man had an affair with your sister."

"Affair, shit. Raped, used, sent Sandra away when she was so shamed and scared there wasn't no choice. Like a whole bunch of girls before her. I never even saw her — not a good-bye, nothing."

"Hard."

"You don't know about hard. Now you need to leave."

"Tell me about Sandra."

Hector Mara hefted his PalmPilot. "I got a salvage yard to manage, gringo. Books to balance. Don't help when the fucking police keep me tied up the whole day, neither. Why don't you leave me alone?"

Hector tried to ignore me. He started writing.

I drank my beer. Behind us, Shelly Lares sang about her broken corazon.

"Was Sandra happy married to Sanchez?"

Hector's PalmPilot clattered on the bar. "Chingate. What the fuck you want, man? Why do you care?"

"I like annoying you, Hector. It's so easy."

Hector stared at me.

I pointed my bottle at him and fired off a round.

"You fucking insane, gringo."

"Tell me about your sister and I'll leave."

Hector glanced across the room. The men at the tables were bragging about greyhound races. One of the locos at the back booth laughed and the pretty Latina squealed in protest. They didn't seem to be paying us much mind. Hector Mara curled his large brown fingers into his palm one at a time.

Tattoos of swords and snakes on his inner arm rippled. "You want the story? I claimed a rival set to Zeta Sanchez when I was fourteen. Chich Gutierrez, he was one of my older vatos. We wer

e a shitty little set but we thought we were bad. Then one night Zeta and some of his homeboys cornered me at the Courts, said I could die or switch claims. If I switched, I could tell them where to shoot me."

"Your leg," I guessed.

He nodded, traced his fingers over the scar tissue above his knee.

"I did that for one reason, man. I looked at Sanchez and I knew he had the kind of rep I needed for me, my family. Once I was down with Zeta, I got respect. My kid sister Sandra got respect. People left her alone. That was important to me, gringo. Real important."

Hector looked at me to see how I was taking the story so far, maybe to see if the gringo was laughing at him inside.

Apparently I passed the test.

"Sandra wanted to be a poet," Hector said. "You believe that? She never claimed no girl posses when we lived in the Courts. Couldn't stand up for herself. Me claiming Sanchez was all that saved her. Then when we were about sixteen, our mom got busted for dealing. Me and Sandra moved out to my grandmother's place."

"The property on Green Road."

Mara nodded. "For a couple of years I had this stupid idea maybe Sandra was going to make it. Farm life. New school. Perfect for her. She never got into trouble. Made it all the way through high school. Even started college before Zeta got interested in her, you know — in a new way. Zeta decided it was a good match."

"And was it?"

Hector turned his beer bottle in a slow circle. "Zeta was old-fashioned. Didn't want his wife going to college. But he was good to Sandra. Looked out for her."

"You believe that?"

More silence. "She and Zeta would've worked things out, wasn't for the Brandons. After the Old Man caught her, she didn't have no choice but to take his money and run. Sanchez would've killed her for what she did, her fault or not. But, man — it could've been different for her. She almost made it out."

"And you?"

"What about me?"

"Did you make it out?"

Hector smiled sourly. He dabbed his finger in the circle of sweat at the base of his beer, smeared a line of water away from the bottle. "I'm a man. Ain't the same for me."

The Blood of Olympus

The Blood of Olympus The Lightning Thief

The Lightning Thief The Hidden Oracle

The Hidden Oracle The Dark Prophecy

The Dark Prophecy The Sea of Monsters

The Sea of Monsters The Sword of Summer

The Sword of Summer The Lost Hero

The Lost Hero The Ship of the Dead

The Ship of the Dead The Burning Maze

The Burning Maze The Battle of the Labyrinth

The Battle of the Labyrinth The Hammer of Thor

The Hammer of Thor The Last Olympian

The Last Olympian The Red Pyramid

The Red Pyramid The Maze of Bones

The Maze of Bones The Son of Sobek

The Son of Sobek The Titans Curse

The Titans Curse The Staff of Serapis

The Staff of Serapis The Crown of Ptolemy

The Crown of Ptolemy Big Red Tequila

Big Red Tequila Percy Jackson: The Complete Series

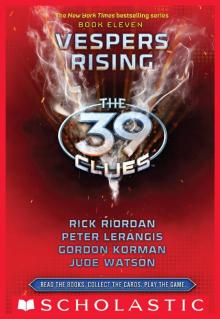

Percy Jackson: The Complete Series Vespers Rising

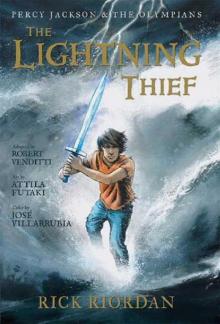

Vespers Rising The Lightning Thief: The Graphic Novel

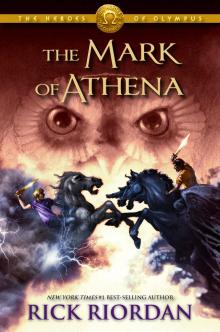

The Lightning Thief: The Graphic Novel The Mark of Athena

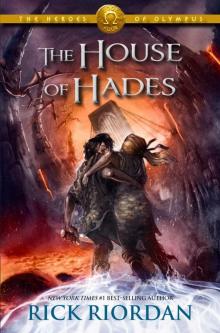

The Mark of Athena The House of Hades

The House of Hades The Son of Neptune

The Son of Neptune The Demigod Diaries

The Demigod Diaries The Serpents Shadow

The Serpents Shadow The Titan's Curse pjato-3

The Titan's Curse pjato-3 The Demigods of Olympus: An Interactive Adventure

The Demigods of Olympus: An Interactive Adventure The Tyrant's Tomb

The Tyrant's Tomb The Demigod Files

The Demigod Files Percy Jackson and the Battle of the Labyrinth

Percy Jackson and the Battle of the Labyrinth The Throne of Fire

The Throne of Fire The Serpent's Shadow (The Kane Chronicles, Book Three)

The Serpent's Shadow (The Kane Chronicles, Book Three) Mission Road

Mission Road The Devil Went Down to Austin

The Devil Went Down to Austin The Tower of Nero

The Tower of Nero The Heroes of Olympus: The Complete Series

The Heroes of Olympus: The Complete Series Rebel Island

Rebel Island The Trials of Apollo Camp Jupiter Classified: A Probatio's Journal

The Trials of Apollo Camp Jupiter Classified: A Probatio's Journal Percy Jackson's Greek Gods

Percy Jackson's Greek Gods The Last King of Texas

The Last King of Texas The Throne of Fire kc-2

The Throne of Fire kc-2 Magnus Chase and the Sword of Summer

Magnus Chase and the Sword of Summer Maze of Bones - 39 Clues 01

Maze of Bones - 39 Clues 01 Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard, Book 2: The Hammer of Thor

Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard, Book 2: The Hammer of Thor Kane 2 - The Throne of Fire

Kane 2 - The Throne of Fire The Last Olympian pjato-5

The Last Olympian pjato-5 The Battle of the Labyrinth pjato-4

The Battle of the Labyrinth pjato-4 From Percy Jackson: Camp Half-Blood Confidential: Your Real Guide to the Demigod Training Camp (Trials of Apollo)

From Percy Jackson: Camp Half-Blood Confidential: Your Real Guide to the Demigod Training Camp (Trials of Apollo) For Magnus Chase: Hotel Valhalla Guide to the Norse Worlds: Your Introduction to Deities, Mythical Beings, & Fantastic Creatures

For Magnus Chase: Hotel Valhalla Guide to the Norse Worlds: Your Introduction to Deities, Mythical Beings, & Fantastic Creatures Southtown tn-5

Southtown tn-5 From Percy Jackson_Camp Half-Blood Confidential

From Percy Jackson_Camp Half-Blood Confidential The Lightning Thief pjatob-1

The Lightning Thief pjatob-1 The Sea of Monsters pjatob-2

The Sea of Monsters pjatob-2 For Magnus Chase_Hotel Valhalla Guide to the Norse Worlds

For Magnus Chase_Hotel Valhalla Guide to the Norse Worlds Percy Jackson and the Bronze Dragon

Percy Jackson and the Bronze Dragon Percy Jackson: The Complete Series (Books 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Percy Jackson: The Complete Series (Books 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) The Mark of Athena (The Heroes of Olympus, Book Three)

The Mark of Athena (The Heroes of Olympus, Book Three) The Heroes of Olympus: The Demigod Diaries

The Heroes of Olympus: The Demigod Diaries The Last King of Texas - Rick Riordan

The Last King of Texas - Rick Riordan Percy Jackson and the Sword of Hades

Percy Jackson and the Sword of Hades Brooklyn House Magician's Manual

Brooklyn House Magician's Manual The Kane Chronicles, Book One: The Red Pyramid

The Kane Chronicles, Book One: The Red Pyramid The Trials of Apollo, Book Three: The Burning Maze

The Trials of Apollo, Book Three: The Burning Maze The Demigods of Olympus

The Demigods of Olympus Big Red Tiquila - Rick Riordan

Big Red Tiquila - Rick Riordan Demigods and Magicians

Demigods and Magicians Percy Jackson and The Stolen Chariot

Percy Jackson and The Stolen Chariot The Mark of Athena hoo-3

The Mark of Athena hoo-3 From Percy Jackson: Camp Half-Blood Confidential: Your Real Guide to the Demigod Training Camp

From Percy Jackson: Camp Half-Blood Confidential: Your Real Guide to the Demigod Training Camp The House of Hades hoo-4

The House of Hades hoo-4 The Devil went down to Austin tn-4

The Devil went down to Austin tn-4 9 from the Nine Worlds (Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard)

9 from the Nine Worlds (Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard) The Trials of Apollo, Book One: The Hidden Oracle

The Trials of Apollo, Book One: The Hidden Oracle The Serpent's Shadow kc-3

The Serpent's Shadow kc-3 The Son of Neptune hoo-2

The Son of Neptune hoo-2 The widower’s two step tn-2

The widower’s two step tn-2 The Lost Hero hoo-1

The Lost Hero hoo-1